Common Values: how clay can play a part in building communities

Crafts Magazine invited us to write a piece based on our book, Clay in Common, for their July/August issue. Common Values describes how clay can play a part in building communities.

“Look at what everyone’s made. It’s brilliant!”

“Once you have made something in clay, it’s just something that comes back to you. It’s sort of in the DNA of your hands.”

(Clayground participants, 2018)

In 2007, artists Clayground Collective set out to explore the question: if clay studies are disappearing in schools and colleges, why are they still important? If they are, how do we pass them on? Going beyond development of the ceramic artists of tomorrow Clayground looked at the role of clay, in not only passing on skills, but in connecting with natural resources and strengthening communities’ capacity to learn.

Craft skills have been central throughout evolution to learning, adaptation and survival. Crafting tools to fashion materials is said to be the starting point for development of language and concepts, hence of learning. Our brains, scientists say, are as much in every part of our body as in our heads. Neurophysiologists remind us there are ten times more channels of information going from our hands to our brains as in the other direction. We move, not to move the world, but to generate sensory feedback[1] enabling us to sense and adapt to the realities of the material world. Making still matters.

Yet policy-makers in the UK and other post-industrial economies see no economic or educational logic for investing in craft skills when manufacturing has largely been outsourced to countries with cheaper labour costs. Academic thinking in schools is privileged over hand skills. An increasingly digital world reinforces this bias. Timetable hours and teacher training for craft and clay are cut in this climate, with facilities and space put to new purposes.

Paradoxically, the decline of clay classes in formal education contrasts with a resurgence of interest amongst voluntary learners. Classes and spaces are proliferating. This market response however only reaches those who can afford to sign up to classes or studio membership.

Where do adults and young people without financial resources engage with clay for the first time, even gain the idea that making is pleasurable and can lead to all kinds of opportunities in life? Other spaces and places in the civic sphere take on new significance as a result.

In the world of arts and craft institutions, museums and galleries, the word ‘community’ most usually denotes programmes for people who are outside the mainstream, fulfilling to some extent the need for open access to all.

A real sense of ‘community’ however is made through people from all points on the economic and ability spectrum working alongside one another on equal terms, during festivals and community celebration. Clay is an ideal medium to create such forms of interaction and has links to cultural tradition the world over. Formed millennia ago, clay is readily shaped by everyone, whatever their age, background, culture or ability. Makers make their mark on it today in a specific time and place imprinting shared cultural memory.

Intergenerational and intercultural activity created with clay in the civic sphere can be called a ‘commons’ as distinct from the market or the state. David Bollier, American policy strategist, describes the commons as:

‘A social system for long-term stewardship of resources that preserves shared values and community identity. Our collective wealth includes the gifts of nature, civic infrastructure, cultural works and traditions, and knowledge….The wealth that we inherit or create together and must pass on, undiminished or enhanced, to our children.’

A commons is not separate from the capacity to engage in ‘commoning’ finding ways to express, maintain and share skills, values and knowledge or manage shared resources. In a world under pressure, large quantities of clay such as Clayground supplies enable communities to reclaim the centre of cities for making and shared imagining rather than shopping.

Clayground mass-making events happen over one or two days such as in the centre of Blackburn with 3000 people as part of the Festival of Making. For some, the depth of experience becomes portable, sparking activities elsewhere in other communities. Participation has informed other initiatives in London, Stoke, Birmingham, Cornwall, Delft (NL) and Charlotte (USA).

Clay is common. We hold it in common and with it can create a commons. It is abundant and universal, a medium to be seized with both hands to build resilient and adaptive communities. It is hoped its value will be recognised soon as an essential part of learning in schools and opportunity beyond.

Clay in Common: A Project Book for Schools, Museums, Galleries, Libraries, and Artists and Clay Activists Everywhere, Julia Rowntree and Duncan Hooson, 2018, Triarchy Press.

[1] Roger Lemon, Neurophysiologist, at Clayground Collective’s Thinking Hands? Symposium, Central Saint Martins, 2014.

Don’t forget if you’d like to receive more news from us and see things that catch our interest, you can follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

Twitter: @Clayground_Co

Instagram: @Claygroundcollective

-

Pandemic clay action!

18th Aug 21

-

The Volcano and the Microbes: interaction between geology and biology

4th Jun 21

-

How to Write a Resume for a Job: Geologist

8th Mar 21

-

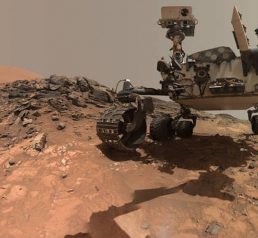

Perseverance: a new NASA rover continues to follow Martian clay

2nd Aug 20

-

Research into clay provides clues as to how much water there was on Mars

18th Sep 19

-

22 Hands: British Ceramics Biennial Commission

12th Aug 19

-

Clayground Summer Events

24th Jun 19

Thames foreshore fragments and visual references

4th Dec 12

How is clay formed? Is it inorganic or organic?

10th Sep 12

CLAY FROM AROUND THE WORLD

3rd Aug 11

Clay Cargo 2014 Collection: the Thames Foreshore

15th Dec 14

Clues to life on Mars likely to be found in clays, Javier Cuadros

5th Aug 16

Clay Cargo 2013-2015

15th Jun 15

Sessions on the Clay Cargo boat, hosted by Fordham Gallery

9th Mar 15

Civic Spaces, Exhibitions

Museums and Galleries, Regeneration

Maker spaces, Rural Sites

Archaeology

Youth and Adult Community Groups, Professionals

Art Groups, Families, Students

Collaborations, Archaeology Sheets

Commissions, Thinking Hands? Research

Knowledge Exchange